The Jewish history in the Gaza Strip extends for many years, especially in the city of Gaza. It began in the Hasmonean Period, when Yonaton the Hasmonean, brother of Yehuda the Hasmonean, conquered Gaza in 145 CE, and his brother Shimon settled Jews there.

There was a Jewish community in Gaza in the Mishna Period as well. Up to 30 years ago one could see on one of the pillars of the great mosque in Gaza the inscription “Hanania bar-Yaacov” in Greek and in Hebrew, and above was engraved a menorah, with a shofar on one side and an etrog on the other. This was evidence that there used to be a Jewish synagogue on the spot which probably served the Jewish community in the days of the Talmud. This important archeological artifact was discovered in 1870, and was destroyed, most likely by nationalist Arabs, a short time after the Arab riots in Yesha (called by the Arabs ‘Intifada’) in 1987.

During the time of the Talmud, most of the northern Negev was settled by Jews, and it was called ‘Gerartika’ – the Land of Gerar. The Talmud describes Kfar Darom as a spot in the south-west of the area. The sage Eliezer son of Itzhak, identified as a man of Kfar Darom, appears in the tractate of Sota (20b). ‘Darom’ was the name of the city which existed in the spot during the Crusaders – one of the periods when the area blossomed.

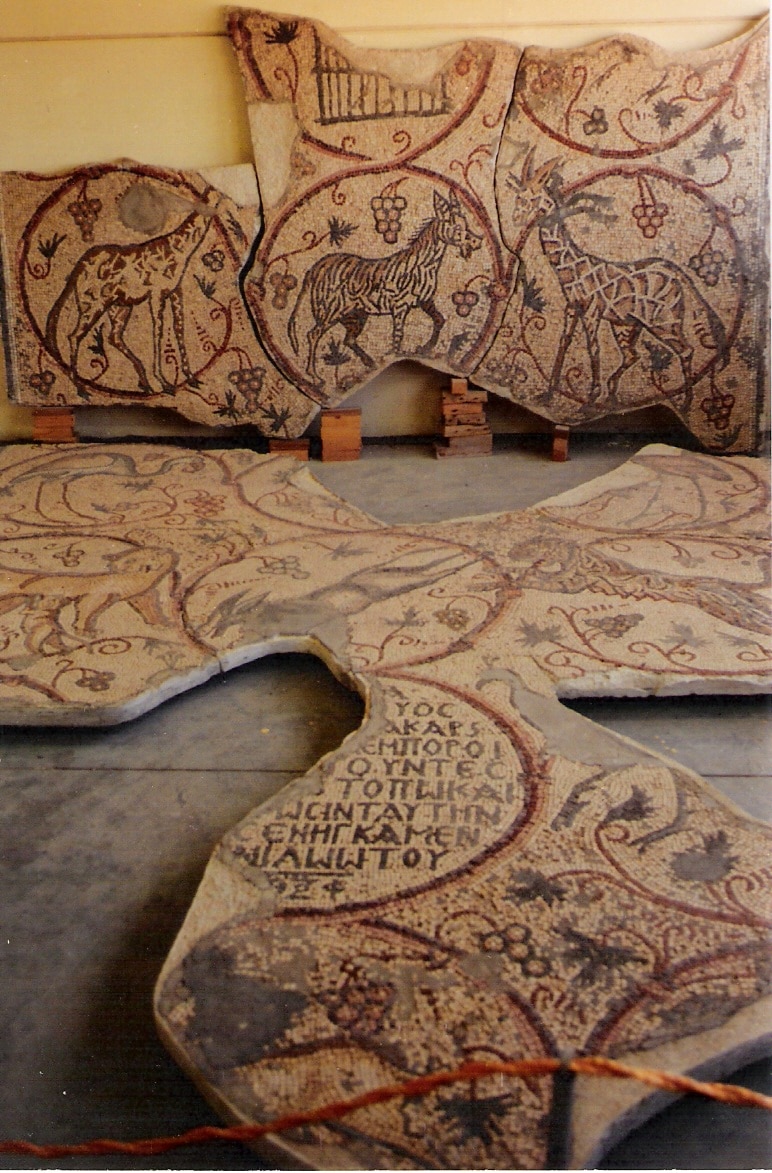

One of the souvenirs from the Jewish community in the days of the Talmud (the Roman-Byzantine period) are the ruins of the ancient Jewish synagogue in Gaza- Maiumas (Gaza-sea); these were revealed on the coast, near the pier of the Gaza port. A large, beautiful mosaic floor was discovered in the synagogue, and at the entrance to the main hall was discovered a figure playing on a harp, enchanting the wild animals. The name “David” appears above it in Hebrew letters.

In the mosaic’s main inscription is written in Greek: “We Menachem and Yeshua sons of Yishai the late are lumber merchants, as a sign of admiration for the holiest site, have donated this mosaic in the month of Laos in the year 569.” The year 569 is according to the special counting of Gaza which was determined in the days of proconsular governor Gabinius, commemorating expelling the Jews from Gaza. If so, the synagogue was built in 508 or 509 CE, meaning during the Roman-Byzantine conquering, and was probably destroyed when conquered by the Muslims, in the 7th century CE, when Gaza-Maiumas was ruined.

In the famous Cairo Geniza are many documents that mention the Jewish community in Gaza after the first Muslim conquest.

Unlike previous periods, we have many testimonies during the Mamluk period on the residence of Jews in the city from a variety of travel books by Jews and non-Jews.

Meshulam of Volterra, a Jewish banker from Florence, visited Gaza in 1481 and wrote that in Gaza there are “Sixty Jewish homeowners and they have a small, beautiful synagogue and vineyards and fields and houses and have already started making new wine. And I was greatly honored, especially by R. Moshe son of R. Yehuda Sephardi, and he stutters a little, and R. Meir Sephardi is a goldsmith … and the Jews dwell on the heights of the land, may the Lord be praised. And there are few houses on the heights of the land, at the top of the Judaica.” It is worth noting that R. Meshulam uses the term ‘Sephardi’ eleven years before the Jews were expelled from Spain. The ‘top of the Judaica’ is the highest hill in the city of Gaza, with a site identified as the grave of the hero Shimshon (Samson). When touring the city today, one discovers that the Arabs call the highest neighborhood ‘Harat al-Yehud’ – the neighborhood of the Jews. R. Meshulam also mentioned the existence of a synagogue in the city. In the highest spot of the city stands a Catholic church, in which broken pieces of ancient marble bars were found in the 19th century. On one piece was discovered the Greek inscription: “For Shalom Yaacov ben Elazar sons in order to give thanks to God for this holy place…”. On another piece in the shape of a column were inscribed the following words: ” The angel who redeems me from all evil will grant me the privilege of ascending to Jerusalem”. It seems that the church was built on the ruins of the city’s ancient synagogue.

Additionally, the eminent Mishna commentator R. Obadiah of Bartenura, who visited Gaza in 1488 wrote that “On the Shabbat all the elders and the Torah scholars came to dine with us, bringing cakes and grapes as their custom, and we drank seven or eight cups before eating, and were happy.”

Among those expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492 were quite a few families who headed to the Land of Israel; some chose to settle in the city of Gaza. The Jewish community in the city grew substantially and numbered some dozens of families. Their economy was based on trade and agriculture. Their employment in agriculture raised many halachic questions, and these can be seen in the various Responsa books.

The hymn “Yah Ribbon Olam” which is still sung today at the Shabbat evening table among Ashkenazi and Sephardi communities, is one of the hymns composed by Rabbi Israel Najara, who officiated as the chief rabbi of Gaza in the 17th century. The period of the Najara rabbis was one in which the Jewish community of Gaza flourished. However, this situation changed quickly due to Nathan of Gaza, the right-hand man of the false prophet, Shabtai Tzvi. The false coronation of Shabtai Tzvi also took place in Gaza.

From the book of travels by the HIDA, Haim Yosef David Azolai, who arrived in Gaza in the month of Shvat 1753 on his way from Hevron to Egypt, we learn that there was a Jewish minyan, and most likely a synagogue as well.

In 1835, the Egyptian ruler of the Land of Israel, Ibrahim Basha, ordered to dismantle the synagogue building at the top of the hill and build from its stones a fortress in the city of Majdal, known today as Ashkelon. The Jewish community of Gaza residing in Hevron hurried to Gaza to take the synagogue’s decorated doors and bring them to Hevron. There they were erected in the ‘Avraham Avenu’ synagogue. Less than a hundred years later, in the 1929 Arab riots, the entire synagogue was destroyed by the Arabs. The beautiful wooden doors disappeared, and it is not clear whether they were burned or stolen. In any event, there was not a trace of them left.

The exact date of the Jews’ return to Gaza is not known. In 1942, Itzhak ben Zvi wrote in his book She’ar Yishuv (1942) that he heard that as early as 1870-1872 Jews were settled in Gaza. Yechiel Bril, editor of the Lebanon newspaper, who visited in Gaza in 1883, told that the Jewish community had been renewed a year previously: “Last year four Jewish families settled from among those who came from the Russian desert to the Holy Land. These people were traders or middlemen in their homeland and came to the Holy Land to work the land…”.

In 1885, at the height of the First Aliya, Ze’ev Kalonymus Wissotzky visited the Land of Israel (July 8, 1824 – May 24, 1904); one of the heads of the Hovevei Zion movement in Russia and the famous tea trader whose name has remained associated with tea until today. Wissotzky came up with a ‘revolutionary’ idea – to establish urban Jewish communities in Arab cities such as Lod, Nazareth, Shechem, Gaza, Ramla and Bethlehem. It was agreed that the first three cities to which settlement nucleuses would go (“minyan” as they were called at the time) would be Gaza, Lod and Shechem. The nucleus going to Gaza was the largest. It was led by Avraham Haim Shalosh and Hacham Nisim Elkayam, the son of Rabbi Moshe Elkayam – one of the leaders of the community in Jaffa. At the end of 1886 there were already more than 30 Jewish families in Gaza. The Jews in Gaza made a living from trade and from traveling sales. Everyone was gainfully employed and lived well. The community was very religiously observant. It had two butchers (each according to Jewish religious law), a rabbi who also taught in the Talmud Torah, its own cemetery, and a mikva.

In 1908, Haham Elkayam visited Jerusalem and met with Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. The latter suggested to Elkayam to establish a modern Hebrew school in Gaza like there was in Jerusalem and Jaffe. When Elkayam brought Ben-Yehuda’s suggestion before his city’s residents the public split into those for it and those against. Elkayam, who supported the suggestion, persuaded the majority of the people to follow him, and with the help of Ben-Yehuda two teachers came to Gaza. The first Hebrew school in Gaza became a fact on May 23, 1910.

The trade industry in Gaza required a banking institution and on May 25, 1914, a bank branch was established in Gaza by the initiative of David Levontin, who was the manager of the Anglo-Palestine bank (the predecessor of the Leumi LeIsrael bank). Avraham Elmaliah was appointed manager of the bank; he had previously served as secretary for the rabbinate and director of the Jewish public schools in Damascus.

World War One broke out at the end of that year. When the Ottomans saw the British army approaching from Egypt to the Gazan area, they quickly banished all the city residents including the Jews. Some of the Jews were even expelled to outside the borders of the country. This is how it was described by the author of the moshavs, Moshe Smilansky: “There were also some Jewish families in Gaza. Already at the beginning of the war they scattered here and there and only three families remained to be expelled. One of them did not forget the heritage of his fathers: he could not save his possessions, but he saved three Torah scrolls from the revolution”. Thus, came to its end an additional chapter of Jewish settlement in Gaza which had lasted for 50 years.

When World War One ended, the British established their rule in the Land of Israel. In the beginning of 1919, the Jewish community started to very slowly renew itself. With its renewal, they also re-established the Jewish elementary school ‘Samson’.

The depletion of the Jewish community in Gaza was caused by economic concerns. In 1927 the Jewish community in Gaza numbered 50 men. They lived within the Arab environment and remained on a friendly relationship with their Arab neighbors. After two years, everything changed. In August 1929, during the Arab riots in Hevron, the Arabs in Gaza similarly tried to harm the Jews in Gaza, and massacre them as had been done to the Hevron Jews. The Jews gathered in a city hotel. With the help of the a-Shawa family which belonged to the aristocracy of Gaza Arabs, the British managed to protect them from the Arab mob besieging the hotel and get them out in the middle of the night by train to Lod, and from there to Tel Aviv.

The story of the Jewish community in Gaza during the 1929 Arab riots was pushed out of the national memory. It does not appear in documents, except for noting the fact that “The Jewish community in Gaza ceased to exist after the 1929 Arab riots”. In the full report of the British Commission of Inquiry (the Shaw Commission) which investigated the 1929 Arab riots at the end of that year, they did not even mention the events in Gaza, and not one Jew from Gaza was invited to testify before the commission.

The Arab riots destroyed the Jewish community in Gaza. All attempts to renew the Jewish community in the city in the following years failed. Gaza became a city ‘clean’ of Jews.